The chaaampiooons!

Ahh, it’s going to feel so good hearing that again.

The UEFA Champions League returns tomorrow with its first batch of group stage games. Zenit St. Petersburg vs. Club Brugge and Dynamo Kiev vs. Juventus kick things off at 12:55 pm Eastern Time, followed by a slew of games from groups E, F, G and H.

Granted, we didn’t have to endure too long of a wait. The 2020 Champions League Final took place just two months ago, and qualifying games for this year’s edition were being contested as recently as September 30.

But weeks feel like months and months feel like years in this pandemic, so cut me some slack if I make it seem as though this competition’s been gone for an eternity. I’ve missed the Champions League, and I’m ready to welcome Europe’s elite cup competition back with open arms.

To celebrate the start of the Champions League’s group stage this week, I thought I’d do what I do best and break down one of my favourite group stage saves of all time. And to do that, we’ll have to rewind to just under a year ago.

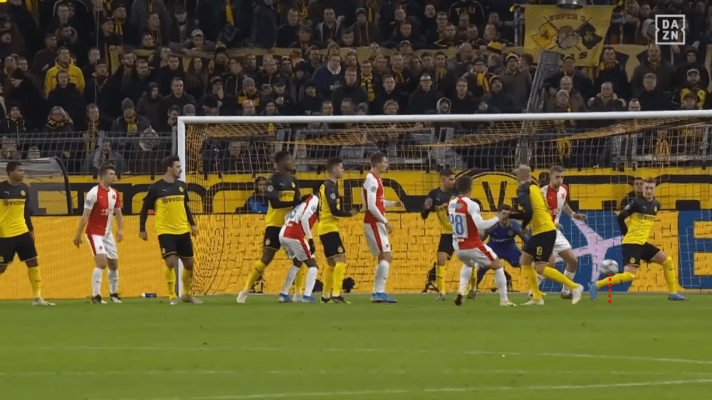

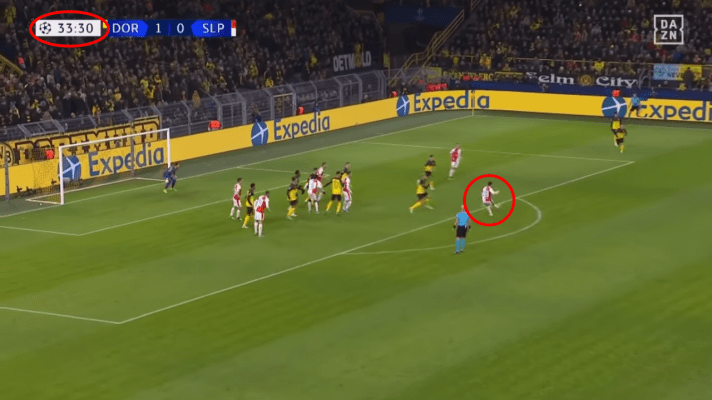

The date was December 10, 2019. Borussia Dortmund were hosting Slavia Prague in the final group stage game of the 2019-20 Champions League. The Germans were up 1-0, but Slavia Prague had a free kick on the touchline of the left side of Dortmund’s box.

The free kick was played low to the outside edge of Dortmund’s box, just central of the goal. Slavia’s Lukáš Masopust met the pass with a one-time effort, and while the initial shot looked manageable, a wicked deflection off of Dortmund captain Marco Reus — which changed both the ball’s flight and pace — made it seemingly impossible for any goalkeeper to handle it.

But Dortmund goalkeeper Roman Bürki, in an example of world-class athletism and acrobatics, had other ideas.

(*Skip to 1:23.*)

It was one of seven saves the Swiss goalkeeper made that day, and it helped preserve a 2-1 win for the hosts. That was an important victory as it ensured Dortmund’s qualification to the Champions League knockout stage — a loss would’ve sent BVB down to the Europa League.

The save, though recent, is already one of the competition’s best saves of all time in my eyes. It is a great example of Bürki’s incredible acrobatics, reactions and adaptability, and I’d dare say that few other goalkeepers in world football would’ve been capable of replicating this stop.

The Shot and its Challenges

The most obvious thing to note about this shot is the massive deflection. As mentioned in the introduction, Lukáš Masopust’s shot was initially travelling close to the ground. but when the ball strikes Marco Reus’s calf, the shot pops into the air and deflects into an arching motion.

Thanks to the deflection, Masopust’s shot went from a quick, low attempt to a high, arching shot. It went from one extreme height to another, all in under two seconds.

Based on my very rough assumptions — which were calculated by hypothesizing the ball’s height is based on the goal’s height (8 ft) and the height of the standing Mats Hummels (6 ft 4) on the left side of the first screenshot — it seems like the deflection bumped the ball up a good six or so feet into the air.

This is obviously not good news for Roman Bürki, who has to readjust his body to compensate for this extreme change.

It also doesn’t help that the deflection happens not that far away from Bürki’s goal, so he doesn’t have much time to readjust himself.

Masopust takes the shot from about a yard away from the edge of the 18-yard box (20 yards away from the goal line). Given Bürki is a couple of steps off of his line, I’m going to assume that he was about two yards off of his line and about 18 yards away from Masopust when the latter struck this attempt.

The deflection then happens around the penalty-spot area, which is 12 yards away from the goal line. Given Reus was a few steps deeper than the penalty spot, I’m going to say he was around 10 yards away from the goal line and 8 yards away from Bürki when the ball deflected off of him.

So to recap, Bürki was about 18 yards away from Masopust when the latter struck the shot and about 8 yards away from Reus when the shot deflected off of his teammate.

This obviously doesn’t give Bürki much time to process the deflection and react accordingly, especially because the speed of both the ball and Bürki’s own natural ability to process moving objects are working against him.

I couldn’t find a specific stat to shed light on this, but it seems to be generally accepted that the average footballer can kick a ball at a speed between 80 km/hr and 100 km/hr, or between 87,489.1 yd/hr and 109,361.3 yd/hr.

To break that down into smaller numbers, that’s the equivalent of kicking a soccer ball at a speed between 24.3 yd/s and 30.4 yd/s. Keep in mind that Bürki was only about 18 yards away from Masopust when the shot was struck and 8 yards away from Reus when the ball was deflected.

Granted, shots gradually lose speed as they travel towards the goal, but that doesn’t mean they’re not covering a lot of ground in very little time. In this scenario, for example, while Masopust’s shot is slowed down by the deflection, it’s still moving fast enough that it’s able to reach Bürki’s goal in just over a second, deflection and all.

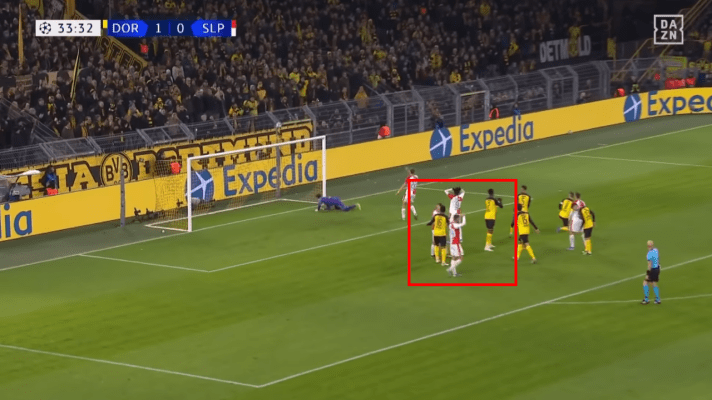

As the game clock shows us, Masopust strikes the ball at minute 33:30. The deflection happens soon after, and then Bürki makes contact with the ball at the 33:31 mark.

In under two seconds, Bürki had to process Masopust’s shot (which is approaching him at a brisk pace) and the deflection — which research suggests he’s seeing one-tenth of a second later anyway. That’s not a lot of time for Bürki to process everything in.

And as if the extreme change in the shot’s trajectory, the speed of the shot and the little time Bürki has to react to all of this aren’t enough, Bürki’s chances of stopping this attempt are made even more difficult by the state the deflection leaves his set shape in.

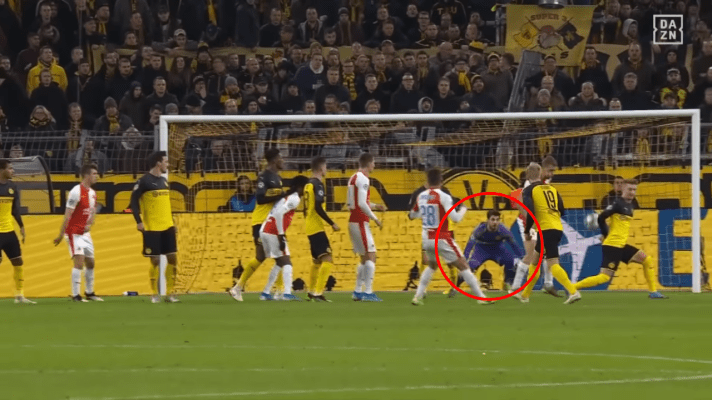

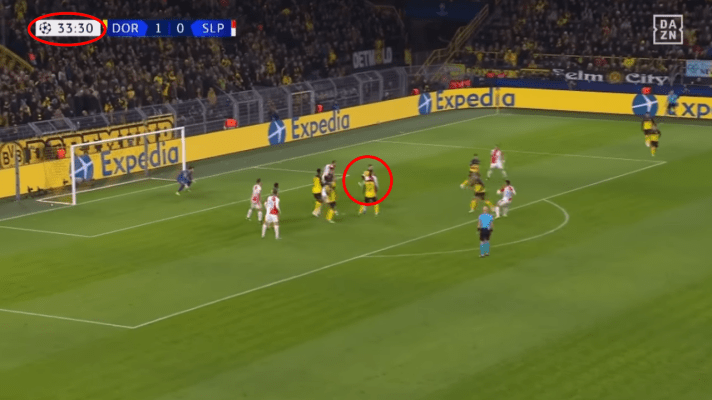

Let’s take a look at Bürki moments after the deflection.

Here, Bürki is still processing the deflection. His body is still reacting to Masopust’s initial attempt — a low shot — so his weight is shifted downwards. His momentum is pushing him towards the ground; his upper-body is moving towards the ground, his legs are giving way for his body to hit the ground, and his hands are moving downwards.

As the ball pops upwards, Bürki’s body is still in the process of reacting to a low attempt. It isn’t until the ball is near the peak of its arch that Bürki has fully processed the deflection and is getting ready to react to it.

Unfortunately, at this point, Bürki’s body is grounded; most of his lower body is spread on the ground, he’s not in a good set shape on his feet, and he has both a hand and a knee touching the ground, which hinders his ability to get a strong push-off.

By all accounts, this should mean that Bürki is condemned to watching the shot sail over his head.

Obviously, Bürki’s not in this position through any fault of his own. But unfortunately, deflections are some of the hardest shots to deal with, and this particular deflection is a clear example of that.

Given Bürki’s state as the ball drops, along with the deflection itself and the speed and distance of the shot, it would’ve been fair for any football fan to think Bürki was done for.

The Save

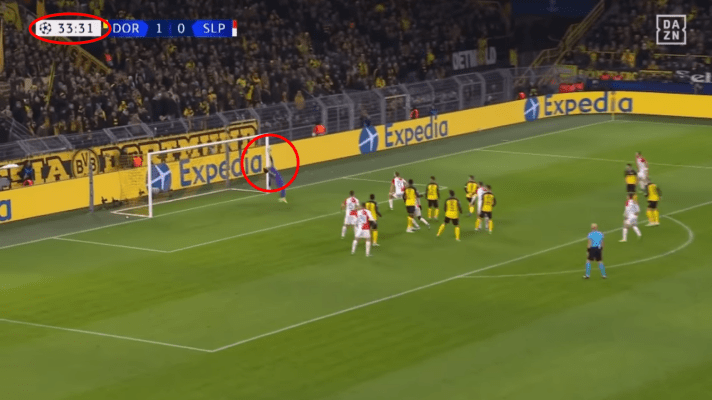

But as the ball drops, a goalkeeping miracle happens. Roman Bürki, now with no downward momentum to fight against, takes a step with his right leg and pushes off into the air. In the process, he also swings his right arm at the ball, getting just enough of the ball to swat it over the bar.

Bürki’s stop didn’t go unnoticed. Borussia Dortmund fans applauded their goalkeeper, and on the pitch, both Bürki’s teammates and opponents couldn’t hold back their reactions.

But how did Bürki do it? How did he make this fantastic save from a position that made it nearly impossible for him to do so? Well, there are a few things that helped Bürki make this stop.

Firstly, Bürki had to focus on stopping his downward momentum from carrying him any closer to the ground. As I mentioned above, Bürki’s body weight shifted downwards as he reacted to Lukáš Masopust’s shot. His momentum was pushing him downwards and his legs were giving way for his body to react in a downward motion.

This is great for stopping a low attempt, but it’s not great for stopping a high attempt — which is what Masopust’s low shot became after the deflection. So, in order to readjust to the shot’s new trajectory, Bürki had to stop his body’s downward movement.

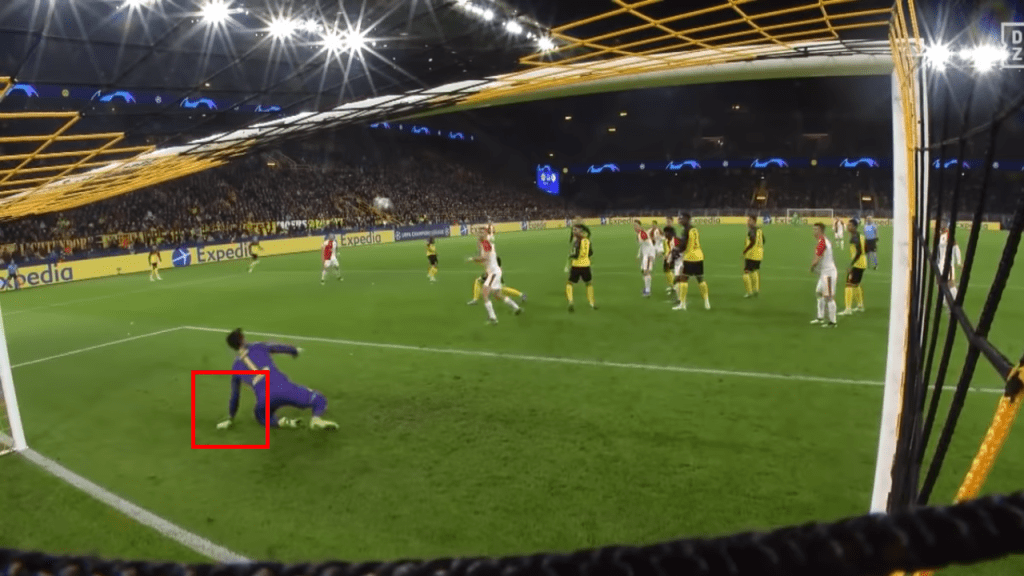

To do that, Bürki places his left hand on the ground. This action may seem unimportant, but it’s what stabilizes Bürki’s body, stifles his downwards momentum, and sets himself up for the save attempt.

By using his left arm to stop his body from dropping further, Bürki is able to stabilize himself and prepare for the next step in the save attempt. Keep in mind, Bürki can’t spring upwards if his momentum is carrying him downwards. He has to stabilize his body first, then react in an upwards manner.

With that said, it becomes clear that had Bürki not stuck out his left arm in this scenario, his momentum would’ve carried him closer to the ground and prevented him from making this save.

After stabilizing his body, Bürki’s next task is to push himself upwards from his position.

This is much easier said than done. As I noted earlier, the deflection essentially grounds Bürki; most of his lower body is sprawled across the ground as a result of the change in trajectory.

It’s very difficult to get a good, vertical jump from this grounded position. Gravity is already working against you, and with your legs in an awkward position, you can’t get as strong of a push-off from the ground as you would’ve had you been standing.

This is why, in Bürki’s case, the step he takes with his right leg is so important. As you can see in the below screenshot, while his left leg is placed completely against the ground, Bürki steps with his right leg. He plants his right foot into the ground and he positions his right leg at a roughly perpendicular angle to the pitch.

This step allows Bürki to push himself off of the ground and fling himself into the air. Even though he’s only using one leg, he’s able to generate strong, vertical force, and this results in a good, upwards lift-off.

Had Bürki not taken this step with his right leg, I highly doubt he would’ve generated the necessary force to push himself a few feet off of the ground and reach this deflected attempt away.

The final step in Bürki’s save attempt has to do with a goalkeeper’s tools of the trade; his arms.

There are two things I’d like to highlight about Bürki’s save attempt involving his arms. Firstly, his arm choice.

As we can see in the replay, Bürki attempts to save this shot using his right arm. As the ball moves towards his goal, Bürki swings his right arm above his head and swats the ball over the crossbar.

In my opinion, Bürki made the correct decision to use his right arm in this scenario. Because Bürki’s body is slightly angled to his left side, the right side of his body is positioned closer to the crossbar, while his left side is positioned closer to the ground.

This means that Bürki’s right arm is more suited to handling a high shot. It’s closer to the high-flying ball than his bottom, left arm. Therefore, it would provide Bürki with the necessary extension and reach needed to turn this shot away.

Furthermore, Bürki’s left arm is already being used to stabilize his position on the ground. So, if Bürki were to attempt to save this shot with his left arm, he would’ve wasted valuable time bringing his left arm up from the ground into the air when he could’ve saved time using his right arm — the one closer to the shot — instead.

Thankfully for Dortmund fans, Bürki made the correct, efficient choice and used his right arm to save this shot.

The other technical aspect I wanted to touch on is Bürki’s arm swing. As we can see in the various mediums, Bürki swung his arm up in an arching motion in order to meet this shot. He didn’t just lift his arm straight up; rather, he swung it over his body in a semi-circular motion.

Though this may not seem like much, I think this arm swing was essential to Bürki’s save attempt because it generated enough power in Bürki’s parry for him to swat this ball comfortably over his goal.

Although Bürki’s push-off generated enough force for the goalkeeper to propel himself into the air, it might not have been enough for Bürki to push the shot upwards. With gravity pulling the ball and body downwards, Bürki needed to generate more force into his save attempt. If he didn’t do so, his save attempt might not have been enough to knock the shot over the goal, even if he got a full hand in front of it.

This is where the arm swing comes into play. By swinging his arm upwards and over his body, Bürki is generating momentum and power into his arm, which strengthens his chances of deflecting this shot away in a proper manner. As he swings his arm upwards, Bürki is building force into his save attempt, and that allows him to parry this shot away with considerable power.

Had Bürki attempted to stop this shot with a stiff arm, it’s likely he wouldn’t have generated enough force into his parry to stop this shot. This is because a stiff arm doesn’t generate a lot of power on its own — most of the power it generates comes from whatever force the body’s upward momentum has. And in this scenario, because Bürki likely didn’t generate enough force to fight gravity and push this shot high enough, using a stiff arm to save this attempt might not have been enough to prevent a goal from happening.

But by swinging his arm upwards, Bürki built off of the momentum his body had generated and built enough force into his arm that he was able to swat the ball away cleanly, despite starting from a weak, grounded position.

Though they may not seem like much, these decisions — stabilizing the body using the left arm, pushing upwards using the right leg, and swinging at the ball using the top hand — helped Bürki turn a nightmarish situation into a manageable scenario.

I sometimes jokingly refer to Roman Bürki a trapeze artist due to his flexibility and nimbleness, but jokes aside, the Swiss international is very acrobatic and agile. Though, his feats are at times more reminiscent of a Cirque du Soleil act than a display of goalkeeping.

Yet, it works. Bürki finished second in clean sheets kept in the Bundesliga last season — he was one of only two goalkeepers to keep a clean sheet in over 40% of German league appearances. He also made 22 saves in last season’s UEFA Champions League group stage, which were more saves made than the likes of reigning champions Alisson Becker and eventual champion Manuel Neuer.

Bürki has missed Borussia Dortmund’s last three matches, though he’s expected to be in the BVB’s line-up for their opener against Lazio. The Germans are tipped to qualify out of their group, though none of their Group F opponents — Lazio, Zenit Saint Petersburg and Club Brugge — should be considered pushovers.

If Dortmund expect to push on to the knockout rounds, they’ll likely have to call on their athletic Swiss goalkeeper one or two times, similar to how they called upon his services a year ago against Slavia Prague.

Mouhamad Rachini is a journalist and goalkeeper enthusiast. You can reach him on Twitter via @BlameTheKeeper.

Gread Article

LikeLike